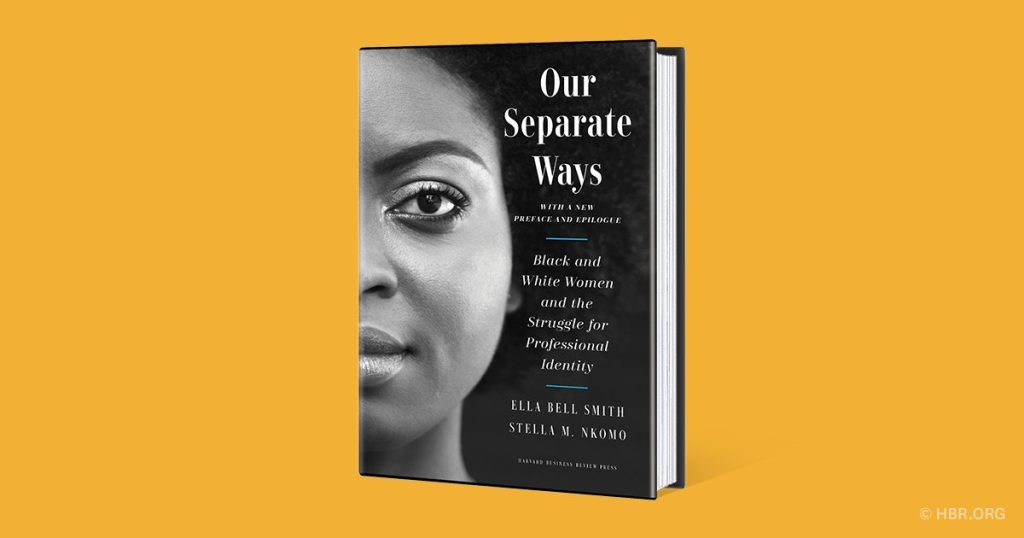

Recently I came across this book, “Our separate ways: Black and White women and the struggle for professional identity” by Ella Bell Smith and Stella M. Nkomo which was the second edition published last year of the earlier edition from 20 years ago.

The main aim of this book was to compare the professional experiences of Black and White women and as one can guess from the title of the book, how it varies significantly. They highlight the intersectionality of gender and race, something we read and discuss a lot in the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) space. The authors contrast the “concrete wall” built on this intersectionality when they see the low proportion of Black female managers (“virtually invisible”) with the “glass ceiling” constraining White women. In 2019, White women held about 32% of the senior management positions in the US compared to 4% of African Americans, 4.3% of Latinas, and 2.5% of Asian women.

This new edition of the book is based on 120 interviews of successful Black and White women conducted over a period of eight years to examine their life and career struggles. Some of their major (and unsurprising) findings and subsequent conclusions are:

- Black and White women do not have the same access to power and privilege because of their different positions with respect to the White men who are at the top of the hierarchy.

- Black women face both racism and sexism in the workplace. Therefore, the company initiatives that aim for gender diversity alone cannot solve the challenges faced by the black women.

- White colleagues should support the Black women for their advocacy and advancement in the workplace. Many narratives showed that their White supervisors did not utilise their talents or gave meaningful assignments despite their proven competence and qualifications.

- Black women want to be themselves and express their cultural identity and not suppress it in any way to merge in with the majority.

- Companies need to support networks of both Black and White women. And these networks need to build constructive bonds with each other.

- Giving back to the Black communities is a vital priority of Black women and it can be an important way to attract and retain their talent.

One of the most striking parts of this book was the extreme honesty of the writers and the women who were interviewed. They did not flinch from uncomfortable conversations around race and gender. For example: “Black women often lament that while white women may speak out against sexism, they do not bring the same energy to confronting racism. For many white women confronting the possibility of their racism is not only agonizing but also often incomprehensible” (p. 259.)

How are the findings and conclusions from this book relevant for the Indian context?

Gender is one of the most common topics of DEI that Indian companies discuss during their diversity initiatives. However, it rarely leads to conversations on intersectionality beyond socio-economic or class backgrounds or sometimes disability.

Topics of caste and religion are automatically rejected by such companies when DEI practitioners and advocates touch upon them. They are rejected, in spite of overwhelming evidence of discrimination against people based on these two identities in general life and at times in the workplace. There is little research for these two supposedly taboo topics in in the workplace but even that limited research shows a clear picture of favoritism and/or discrimination.

A recent research study carried by the LedBy Foundation found significant hiring bias against Muslim women. This study was carried out for a period of over eight months with symmetric (identical content) dummy profiles of Hindu and Muslim women names on Naukri.com and LinkedIn. The profile with the Hindu name received double the number of call backs compared to the Muslim name. Similarly another study found that caste bias is rampant in mergers and acquisitions in the private corporate sector in India and interestingly these companies who show this caste affinity perform slightly worse in returns than the ones who do not enter into same-caste deals.

But most companies do not want to ruffle the feathers or touch these topics for discussion or diversity initiates with a barge pole. Some say, “I don’t see caste or religion in the workplace or anywhere for that matter”, which has the same negative consequences of race or color-blindness. There is research to show that if organisations’ majority members (White colleagues in this case) emphasise color blindness, it predicts a decrease in engagement and feelings of marginalisation of the minorities plus an increased perception of a biased atmosphere. On the other hand, if multiculturalism (emphasising and celebrating differences) is accepted, it has the opposite effect on minorities in the workplace.

Recently Apple was in the news to became the first tech giant to ban caste discrimination and train managers in caste bias while Google faced flak for canceling a talk on caste discrimination by Thenmozhi Soundararajan, a Dalit rights activist. Most Indian companies do not come out in support of the marginalised groups and this was a comparison that was often evoked during the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, that was supported by Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Twitter openly.

The topics of caste and religion in South Asia are not exactly the same as race in the west, where these open conversations have gained greater traction over time. But they need to happen more openly along with gender, and they have to take into account the voices of the people who have been suppressed on account of these identities and faced substantial challenges at work. This can no longer brushed under the carpet. Companies can learn from the same six findings from this book listed above and view it from the caste and religion angles to achieve greater inclusiveness in their workplace.