Imagine you’re hungry at a party and need to know how much pizza to order. You count your friends but forget to include a few people. When the pizza arrives, those uncounted guests are left hungry.

“What gets counted counts.”

The statement made by feminist geographer Joni Seager is powerful. Like in the party where some people who were not counted missed out on getting pizza, when we look at big-picture statistics like literacy rates and income, non-binary people are often left out because there are no categories that fit them. This means they are not included in societal decisions and are missed when resources are given. I thought a lot about this when researching the differences in literacy rates between genders for an article about financial confidence. It was clear that there is hardly any information about non-binary people whose gender identity doesn’t come under the male or female binary.

Is having “other” as an option enough?

Traditionally on passports, official recognition of gender has been limited to male and female. However, over the past decade, there has been a significant shift towards embracing a third gender option in a few countries, often marked as “X,” “other,” or “unspecified.” Australia led this movement in 2011, and countries like Bangladesh, Canada, and India have followed suit. Despite these efforts, these categories are often too broad and fail to capture the true diversity of non-binary identities.

India’s 2011 Census was the first to include the trans population, estimating that 4.8 million Indians identified as transgender. However, the survey tagged the rest as “other,” assuming them to be transgender without acknowledging the full spectrum of non-binary identities. An approach like this, while inclusive in terms of breaking the binary can fail to understand gender diversity comprehensively.

The lack of accurate data on non-binary individuals has significant consequences. Without proper representation, non-binary people are excluded from societal decisions and resource allocation. This exclusion is evident in healthcare, education, employment, housing, and social security among other benefits. For example, the 2024 Global Gender Gap Report by the World Economic Forum highlights the economic participation and opportunity gap between men and women, but does not account for non-binary individuals. Ensuring equitable opportunities becomes challenging without reliable data on non-binary individuals.

The inclusivity paradox

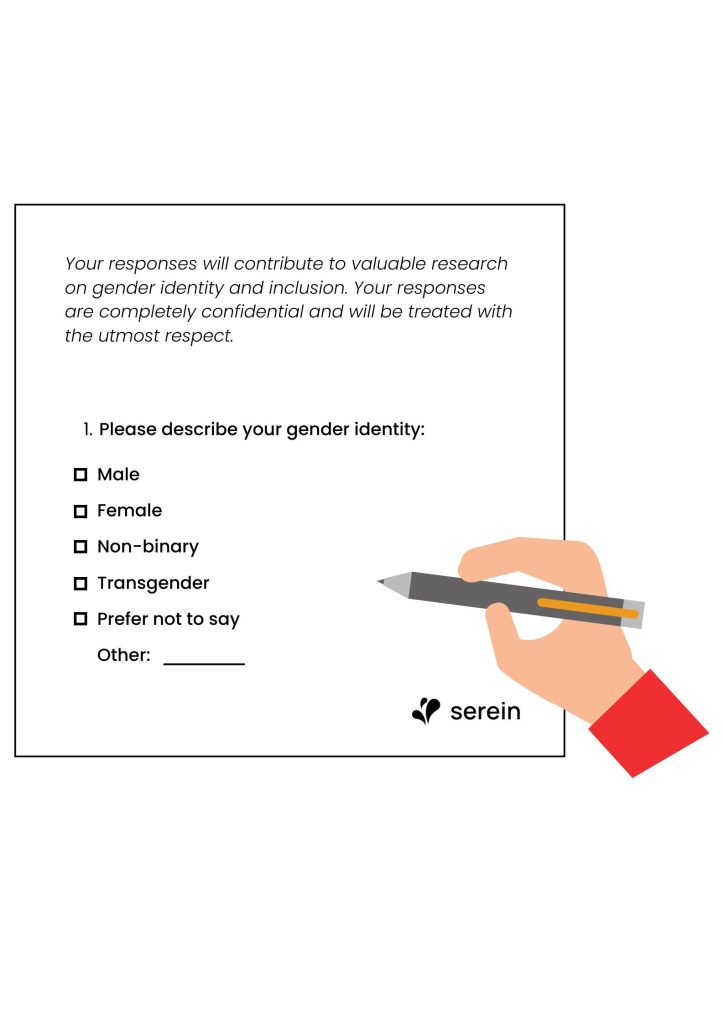

Consequently, non-binary individuals often face a daunting task when asked to select their gender on forms. Even when a non-binary category is offered, individuals may be reluctant to share their gender status due to stigma or the risk of being identifiable in datasets.

The small sample size of non-binary respondents makes it challenging to draw statistically meaningful conclusions, leading to their exclusion from analysis. This exclusion results in what can be termed an “inclusivity paradox.” Allowing individuals to indicate their gender identity without forcing them into binary categories can lead to their data being excluded due to small sample sizes.

What does it take to collect inclusive data?

Collecting inclusive data involves recognising the challenges of studying historically understudied populations and ensuring that the research design asks questions ethically and accurately. Historically, minoritised groups were left out of research due to biases and oversights. Getting the right demographics not only gives us more detailed data but also shows respect for different gender identities.

As researchers Saperstein and Westbrook (2015) note, surveys will keep creating statistical representations that erase important aspects of diversity and probably limit understanding of the processes that perpetuate social inequality unless changed. To address these issues, we must evolve our forms and surveys to collect accurate information and respect different identities.

How can we make forms more inclusive?

- Include open-ended fields for respondents to self-describe their gender and pronouns, allowing a more accurate representation of diverse identities.

- Offer a range of gender options beyond the binary, such as “non-binary,” “genderqueer,” or “prefer not to say,” to encompass various identities.

- Provide clear explanations for how this information will be used and ensure privacy to build trust and encourage honest responses.

A step in the right direction

Various countries have begun adopting legislative frameworks for gender recognition based on self-determination. For example, Argentina’s census questionnaires now include options that distinguish between sex at birth and self-identified gender. For the 2022 census in Scotland, there’s a proposal to include a question about sex followed by a voluntary inquiry asking, “Do you identify as transgender or have a transgender history?” The options provided for this question are “no” and “yes”, along with a description of transgender status.

Including options for non-binary genders in national surveys will help make non-binary individuals more visible and acknowledged. This can also help address the discrimination they often face. It allows for an analysis of power dynamics and their influence on gender roles, access to resources, and the limitations people face in relation to others.

For organisations, collecting gender-inclusive data can improve understanding of workforce and consumer diversity, leading to better hiring practices, inclusive workplace policies, and improved market strategies. This will also result in more precise and comprehensive data on gender identity, helping organisations better understand the experiences and requirements of non-binary employees.

By accurately counting and representing non-binary individuals, we not only acknowledge their existence but also create a more equitable world where everyone, regardless of gender identity, has a seat at the table and a slice of the pizza.

The next article in this series explores the impact of the lack of gender-inclusive data in healthcare.